今天这段依然出自艾伦·图灵(Alan Turing)1936年发表的经典论文《论可计算数及其在判定问题上的应用》(Alan Turing, On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, 1936),具体是文章的第四章。

这一章虽然看着很长很复杂,但实际上就是对前面规则的详细拆解,展示了图灵机不仅可以执行简单的跳转,还可以构建复杂的控制流。相当于图灵定义了一套编程语言,用来更方便地编写图灵机程序。

原文

4. Abbreviated tables.

There are certain types of process used by nearly all machines, and these, in some machines, are used in many connections. These processes include copying down sequences of symbols, comparing sequences, erasing all symbols of a given form, etc. Where such processes are concerned we can abbreviate the tables for the $m$-configurations considerably by the use of "skeleton tables". In skeleton tables there appear capital German letters and small Greek letters. These are of the nature of "variables". By replacing each capital German letter throughout by an $m$-configuration and each small Greek letter by a symbol, we obtain the table for an $m$-configuration.

The skeleton tables are to be regarded as nothing but abbreviations: they are not essential. So long as the reader understands how to obtain the complete tables from the skeleton tables, there is no need to give any exact definitions in this connection.

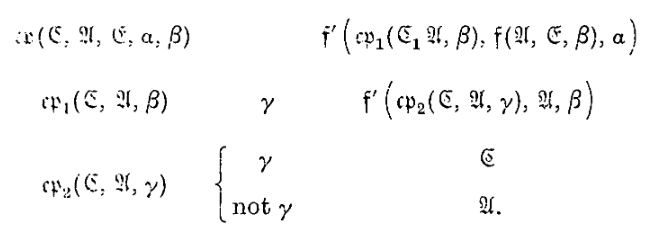

Let us consider an example:

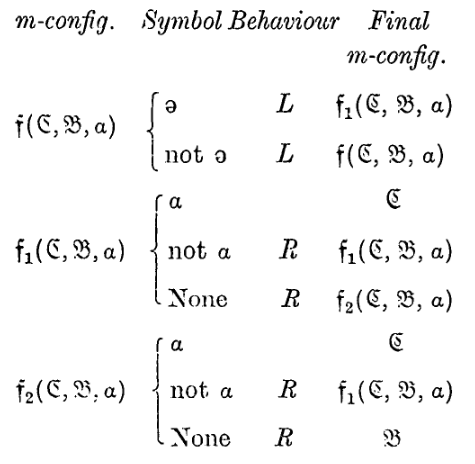

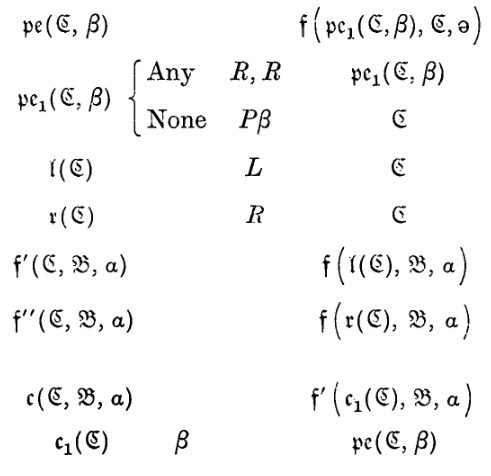

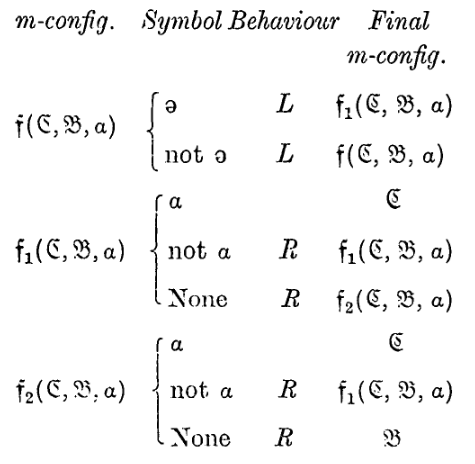

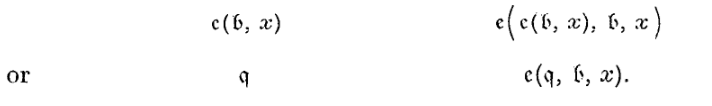

From the m-configuration $f(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$ the machine finds the symbol of form $a$ which is farthest to the left (the "first $a$") and the m-configuration then becomes $\mathfrak{C}$. If there is no $a$ then the m-configuration becomes $\mathfrak{B}$.

If we were to replace $\mathfrak{C}$ throughout by $q$ (say), $\mathfrak{B}$ by $r$, and $a$ by $x$, we should have a complete table for the m-configuration $f(q, r, x)$. $f$ is called an "m-configuration function" or "m-function".

The only expressions which are admissible for substitution in an m-function are the m-configurations and symbols of the machine. These have to be enumerated more or less explicitly: they may include expressions such as $p(e, x)$; indeed they must if there are any m-functions used at all. If we did not insist on this explicit enumeration, but simply stated that the machine had certain m-configurations (enumerated) and all m-configurations obtainable by substitution of m-configurations in certain m-functions, we should usually get an infinity of m-configurations; e.g., we might say that the machine was to have the m-configuration $q$ and all m-configurations obtainable by substituting an m-configuration for $\mathfrak{C}$ in $p(\mathfrak{C})$. Then it would have $q, p(q), p(p(q)), p(p(p(q))), \ldots$ as m-configurations.

Our interpretation rules then is this. We are given the names of the m-configurations of the machine, mostly expressed in terms of m-functions. We are also given skeleton tables. All we want is the complete table for the m-configurations of the machine. This is obtained by repeated substitution in the skeleton tables.

Further examples.

(In the explanations the symbol "$\to$" is used to signify "the machine goes into the m-configuration...")

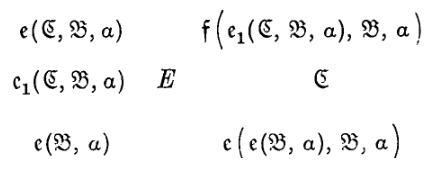

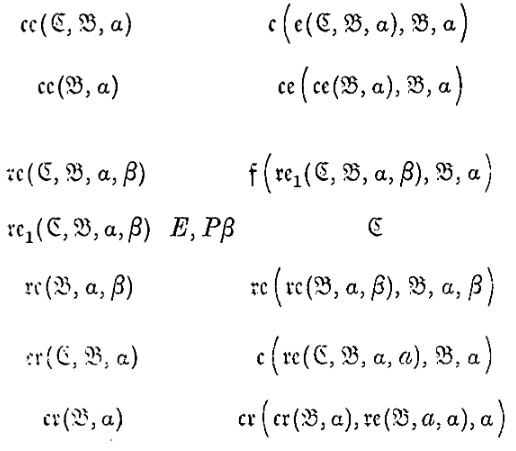

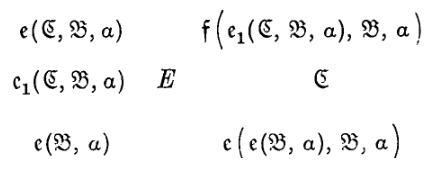

From $e(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$ the first $a$ is erased and $\to \mathfrak{C}$. If there is no $a \to \mathfrak{B}$.

From $e(\mathfrak{B}, a)$ all letters $a$ are erased and $\to \mathfrak{B}$.

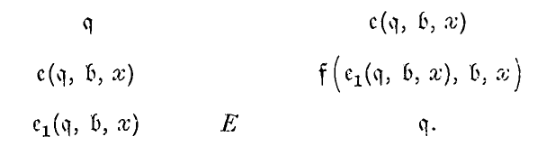

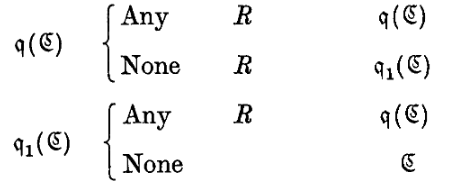

The last example seems somewhat more difficult to interpret than most. Let us suppose that in the list of m-configurations of some machine there appears $e(\mathfrak{B}, a)$ $(= q, \text{say})$. The table is

Or, in greater detail:

In this we could replace $e_1(q, \mathfrak{B}, a)$ by $q'$ and then give the table for $f$ (with the right substitutions) and eventually reach a table in which no m-functions appeared.

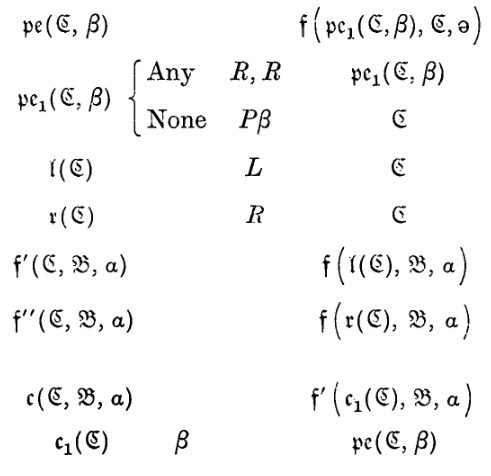

$pe(\mathfrak{C}, \beta)$. From $pe(\mathfrak{C}, \beta)$ the machine prints $\beta$ at the end of the sequence of symbols and $\to \mathfrak{C}$.

$l(\mathfrak{C})$. From $l(\mathfrak{C})$ the machine shifts to the left one square and $\to \mathfrak{C}$.

$r(\mathfrak{C})$. From $r(\mathfrak{C})$ the machine shifts to the right one square and $\to \mathfrak{C}$.

$f'(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$. From $f'(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$ the machine finds the symbol of form $a$ which is farthest to the right (the "last $a$") and the m-configuration then becomes $\mathfrak{C}$. If there is no $a$ then the m-configuration becomes $\mathfrak{B}$.

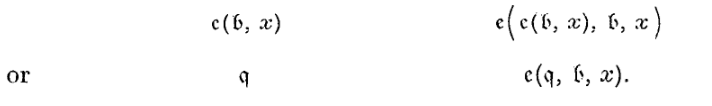

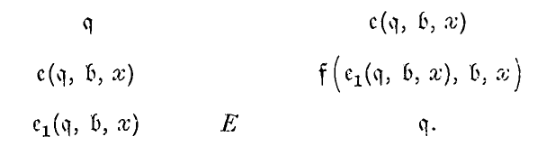

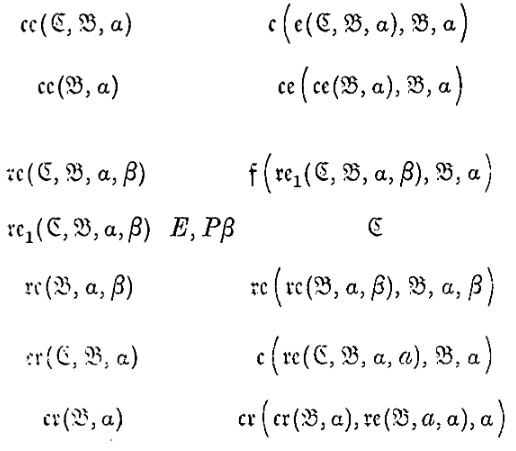

$c(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$. From $c(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$ the machine copies down in order at the end all symbols marked $a$ and erases the letters $a, \to \mathfrak{B}$.

$re(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a, \beta)$. The machine replaces the first $a$ by $\beta$ and $\to \mathfrak{C}$. If there is no $a \to \mathfrak{B}$.

$re(\mathfrak{B}, a, \beta)$. The machine replaces all letters $a$ by $\beta$ and $\to \mathfrak{B}$.

$cr(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$. Differs from $re(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a, a)$ only in that the letters $a$ are not erased. The m-configuration $cr(\mathfrak{B}, a)$ is taken up when no letters $a$ are on the tape.

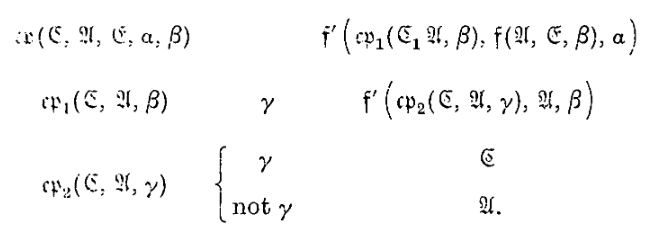

$cp(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{E}, \mathfrak{B}, \alpha, \beta)$. The first symbol marked $\alpha$ and the first marked $\beta$ are compared. If there is neither $\alpha$ nor $\beta, \to \mathfrak{E}$. If there are both and the symbols are alike, $\to \mathfrak{C}$. Otherwise $\to \mathfrak{E}$.

$cpc(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, \mathfrak{E}, \alpha, \beta)$. Differs from $cp(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{E}, \mathfrak{B}, \alpha, \beta)$ in that in the case when there is similarity the first $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are erased.

$cpe(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, \mathfrak{E}, \alpha, \beta)$. The sequence of symbols marked $\alpha$ is compared with the sequence marked $\beta$. $\to \mathfrak{C}$ if they are similar. Otherwise $\to \mathfrak{E}$. Some of the symbols $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are erased.

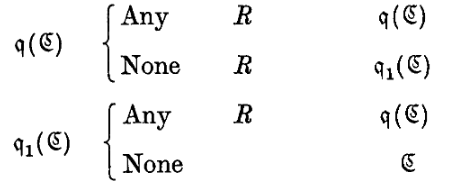

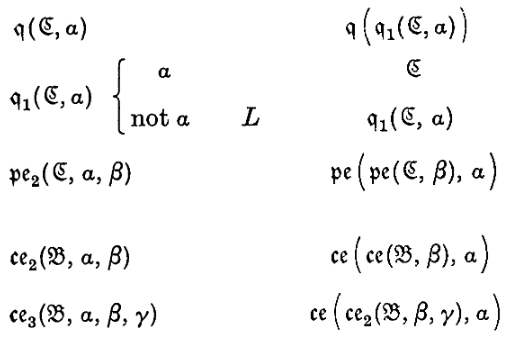

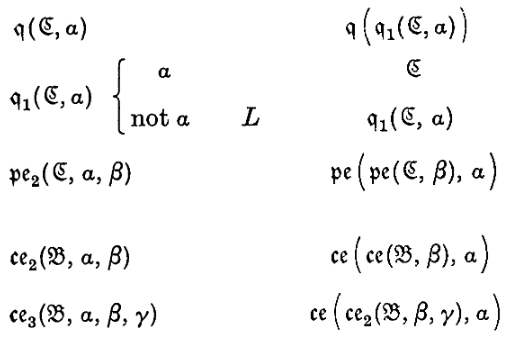

$q(\mathfrak{C}, a)$. The machine finds the last symbol of form $a$. $\to \mathfrak{C}$.

$pe_2(\mathfrak{C}, \alpha, \beta)$. The machine prints $\alpha \beta$ at the end.

$ce_2(\mathfrak{B}, \alpha, \beta, \gamma)$. The machine copies down at the end first the symbols marked $\alpha$, then those marked $\beta$, and finally those marked $\gamma$; it erases the symbols $\alpha, \beta, \gamma$.

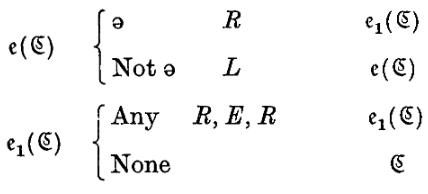

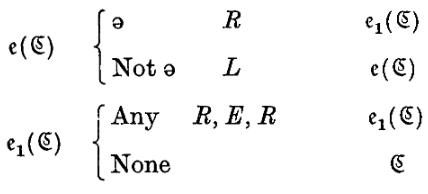

$e(\mathfrak{C})$. From $e(\mathfrak{C})$ the marks are erased from all marked symbols. $\to \mathfrak{C}$.

翻译

4. 缩写表

有一些特定类型的处理过程,几乎所有的计算机器都会用得到,在某些机器中,这些过程被用于许多连接中。这些过程包括复制符号序列、比较序列、擦除某种指定形式的所有符号等。在涉及这样的过程的地方,我们可以通过使用“骨架表”(skeleton tables)来对 m-构型 的表格进行缩写。在骨架表中会出现大写德文字母和小写希腊字母。这两种字母就具有“变量”的性质。将每个大写德文字母替换为对应的 m-构型,将每个小写希腊字母替换为对应的符号,就得到了 m-构型 的表格。

骨架表就只是个缩写:不是必不可少的。只要读者理解如何从骨架表获得完整表格,不需要在一个连接中给出任何确切定义。

让我们考虑一个例子:

从 m-构型 $f(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$ 开始,机器查找最左边的 $a$ 形式的符号(“第一个 $a$”),然后 m-构型变为 $\mathfrak{C}$。如果没有 $a$,则 m-构型变为 $\mathfrak{B}$。

假如我们把 $\mathfrak{C}$ 替换为 $q$,把 $\mathfrak{B}$ 替换为 $r$,把 $a$ 替换为 $x$,我们将得到 m-构型 $f(q, r, x)$ 的完整表格。$f$ 被称为“m-构型函数”或“m-函数”。

在 m-函数中,允许用来替换变量的表达式只有两种:机器的 m-构型和符号。这些可替换的内容必须以某种方式显式地列举出来。列举的内容可以包括像 $p(e, x)$ 这样的表达式(即 m-函数调用的结果);实际上,只要机器用到了任何 m-函数,这类表达式就必须被包括在列举范围内。为什么要坚持这种显式列举呢?因为如果我们不这样做,而只是笼统地声明"机器具有某些已列举的 m-构型,以及所有通过在 m-函数中替换参数而获得的 m-构型",那么通常会得到无穷多个 m-构型。举个例子:假设我们说机器具有 m-构型 $q$,以及所有通过在 $p(\mathfrak{C})$ 中用 m-构型替换 $\mathfrak{C}$ 而获得的 m-构型。那么机器就会有: $$q, \quad p(q), \quad p(p(q)), \quad p(p(p(q))), \quad \ldots$$ 这样无穷多个 m-构型。这与图灵机必须是有限状态的要求相矛盾。

因此,我们的解释规则是这样的:提供给我们的是机器的所有 m-构型的名称(主要用 m-函数的形式表示),以及相应的骨架表。我们需要的是机器 m-构型的完整状态转移表。要达到这个目的,可以在骨架表中反复进行替换操作,将变量替换为具体的值,最终展开得到完整的表格。

进一步的示例。

(在解释中,符号“$\to$”用于表示“机器进入所指向的 m-构型...”)

从 $e(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$ 开始,第一个 $a$ 被擦除并 $\to \mathfrak{C}$。如果没有 $a \to \mathfrak{B}$。

从 $e(\mathfrak{B}, a)$ 开始,所有字母 $a$ 被擦除并 $\to \mathfrak{B}$。

最后一个例子看着比大多数例子更难解释。让我们假设在某台机器的 m-构型列表中出现了 $e(\mathfrak{B}, a)$($=q$)。其表格如下

或者,更详细地展开的表格如下:

在这种情况下,我们可以用 $q'$ 替换 $e_1(q, \mathfrak{B}, a)$,然后给出 $f$ 的表格(进行正确的替换),最终得到一个没有任何 m-函数的表格。

$pe(\mathfrak{C}, \beta)$。从 $pe(\mathfrak{C}, \beta)$ 开始,机器在符号序列的末尾打印 $\beta$,然后 $\to \mathfrak{C}$。

$l(\mathfrak{C})$。从 $l(\mathfrak{C})$ 开始,机器向左移动一格,然后 $\to \mathfrak{C}$。

$r(\mathfrak{C})$。从 $r(\mathfrak{C})$ 开始,机器向右移动一格,然后 $\to \mathfrak{C}$。

$f'(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$。从 $f'(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$ 开始,机器查找最右边的 $a$ 形式的符号(“最后一个 $a$”),m-构型变为 $\mathfrak{C}$。如果没有 $a$,则 m-构型变为 $\mathfrak{B}$。

$c(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$。从 $c(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$ 开始,机器按顺序将所有标记为 $a$ 的符号复制到末尾,并擦除字母 $a$,然后 $\to \mathfrak{B}$。

$re(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a, \beta)$。机器将第一个 $a$ 替换为 $\beta$,然后 $\to \mathfrak{C}$。如果没有 $a \to \mathfrak{B}$。

$re(\mathfrak{B}, a, \beta)$。机器将所有字母 $a$ 替换为 $\beta$,然后 $\to \mathfrak{B}$。

$cr(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$。$cr(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$ 与 $re(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a, a)$ 的区别仅在于字母 $a$ 不会被擦除。当带子上没有字母 $a$ 时,进入 m-构型 $cr(\mathfrak{B}, a)$。

$cp(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{E}, \mathfrak{B}, \alpha, \beta)$。比较第一个标记为 $\alpha$ 的符号和第一个标记为 $\beta$ 的符号。如果既没有 $\alpha$ 也没有 $\beta$,$\to \mathfrak{E}$。如果两者都有且符号相同,$\to \mathfrak{C}$。否则 $\to \mathfrak{E}$。

$cpc(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, \mathfrak{E}, \alpha, \beta)$。与 $cp(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{E}, \mathfrak{B}, \alpha, \beta)$ 的区别在于,当相似时,第一个 $\alpha$ 和 $\beta$ 会被擦除。

$cpe(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, \mathfrak{E}, \alpha, \beta)$。比较标记为 $\alpha$ 的符号序列与标记为 $\beta$ 的序列。如果它们相似,$\to \mathfrak{C}$。否则 $\to \mathfrak{E}$。一些符号 $\alpha$ 和 $\beta$ 会被擦除。

$q(\mathfrak{C}, a)$。机器查找最后一个形式为 $a$ 的符号。$\to \mathfrak{C}$。

$pe_2(\mathfrak{C}, \alpha, \beta)$。机器在末尾打印 $\alpha \beta$。

$ce_2(\mathfrak{B}, \alpha, \beta, \gamma)$。机器在末尾依次复制标记为 $\alpha$ 的符号,然后是标记为 $\beta$ 的,最后是标记为 $\gamma$ 的;它擦除符号 $\alpha, \beta, \gamma$。

$e(\mathfrak{C})$。从 $e(\mathfrak{C})$ 开始,擦除所有标记符号上的标记。$\to \mathfrak{C}$。

逐段解析

1. 骨架表 (Skeleton tables) 的概念

“几乎所有的机器都会用到某些类型的处理过程...我们可以通过使用‘骨架表’大大缩写 m-构型的表格。”

- 模块化编程的雏形:图灵在这里引入了函数(Functions)和子程序(Subroutines)的概念。

- 变量:

- 大写德文字母(如 $\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}$):代表状态变量(Target State)。类似于现代编程中的

return_address或next_function。 - 小写希腊字母(如 $\alpha, \beta$):代表符号变量(Symbol)。类似于函数的参数。

- 目的:避免重复造轮子。比如“向左找到第一个字符 x”这个操作,在复杂的机器中可能要用很多次,只是每次找完之后下一步要做的事情不同。通过定义一个通用函数 $f(\text{找到后的状态}, \text{没找到的状态}, \text{要找的符号})$,就可以复用代码。

2. 示例分析:查找函数 $f$

“从 m-构型 $f(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$ 开始,机器查找最左边的 $a$... 然后 m-构型变为 $\mathfrak{C}$。如果没有 $a$,则... 变为 $\mathfrak{B}$。”

- 功能:这是一个通用的查找(Find)函数。

- 参数:

- $\mathfrak{C}$ (Success State): 找到目标符号后要跳转的状态。

- $\mathfrak{B}$ (Failure State): 没找到目标符号要跳转的状态。

- $a$ (Target Symbol): 要查找的符号。

- 逻辑:

- 一直向左走($L$),直到遇到 $ə$(边界标记)。

- 然后开始向右扫描($R$)。

- 如果遇到 $a$,就跳转到 $\mathfrak{C}$。

- 如果遇到 None(空白)还没遇到 $a$,说明找遍了也没有,跳转到 $\mathfrak{B}$。

3. 递归与无穷状态的避免

“如果我们不坚持这种显式列举... 我们通常会得到无穷多个 m-构型...”

- 递归定义的风险:图灵敏锐地指出了如果允许函数无限嵌套(如 $p(p(p(...)))$),会导致状态数变为无穷大。

- 有限状态机:图灵机必须是有限状态的。因此,虽然我们可以用函数式的方法来描述它,但最终展开后的状态总数必须是有限的。这意味着在设计机器时,不能陷入无限递归的定义。

4. 更多示例:擦除函数 $e$

- $e(\mathfrak{C}, \mathfrak{B}, a)$:

- Erase one:找到第一个 $a$,把它擦掉($E$),然后去状态 $\mathfrak{C}$。没找到去 $\mathfrak{B}$。

- 它是通过调用上面的查找函数 $f$ 来实现的。

- $e(\mathfrak{B}, a)$:

- Erase all:擦除所有的 $a$。

- 实现逻辑:擦掉一个 $a$ 后,递归地调用自己 $e(\mathfrak{B}, a)$ 继续擦,直到找不到为止(跳转到 $\mathfrak{B}$)。

- 这是一个典型的循环(Loop)或递归调用的例子。

总结

图灵引入的“骨架表”有点类似现代意义的函数库,实际上就相当于定义了一套编程语言,用来更方便地编写图灵机程序。这为后面构造极其复杂的“通用图灵机”奠定了工程基础。如果没有这些缩写,通用图灵机的状态表将庞大到无法阅读。但这些表格其实也挺麻烦的。

CycleUser

CycleUser